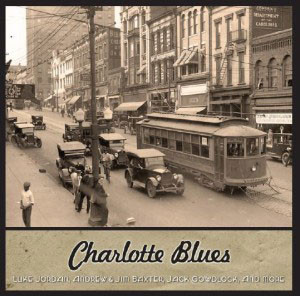

Charlotte Blues: Luke Jordan, Andrew & Jim Baxter, Jack Gowdlock and More (Nehi Records CD NEH06, released 2014 in England).

Charlotte Blues

During the heyday of field recording in the late 1920s and 1930s, Charlotte ranked among the most-visited locations. In fact in the late 1930s it hosted more recording sessions than Nashville.

During the heyday of field recording in the late 1920s and 1930s, Charlotte ranked among the most-visited locations. In fact in the late 1930s it hosted more recording sessions than Nashville.

Why Charlotte? The city emerged in the 1920s as the hub of America’s new textile manufacturing belt, a wholesaling and banking centre whose population swelled from less than 20,000 in 1900 to 100,000 by 1940. It sat astride the Southern Railway, “Main Street of the South,” linking New Orleans, Atlanta, Durham and Washington, D.C. In 1922 WBT radio signed in the air, the second radio station in the South, and by the early 1930s its 50,000 watt signal covered the myriad small cotton farming towns that dotted the rolling hills of the North and South Carolina piedmont region. The combination of good radio and lots of nearby places to play drew musicians from all over the South to perform live on WBT, making Charlotte an attractive stop of record labels seeking talent.

Teams from Victor (later RCA Victor) visited most often. Decca and other labels were represented as well. Famed producer Ralph Peer made the first visits in 1927 and 1931. Artists on those dates included the Carter Family, taking a sojourn from their Virginia home to perform on WBT, plus the rollicking Georgia yellow Hammers string-band, and future Louisiana Governor Jimmie Davis, then best known for his white interpretations of naughty blues.

Peer’s reign at RCA gave way to the equally talented Eli Oberstein, who visited the area several times a year during 1936 – 1938. He recorded first in warehouse space the RCA maintained upstairs in a main street building on South Tryon Street, then at the posh Hotel Charlotte, and finally at the Andrew Jackson Hotel in nearby Rock Hill, S.C. Bill Monroe, the Kentucky mandolinist who would later go on to create and name “Bluegrass” music, was RCA’s most important discovery in these Charlotte sessions. But Oberstein also waxed a host of other notable artists including Fiddling Arthur Smith and the Delmore Brothers, Uncle Dave Macon, J.E. and Wade Mainer, and African American a cappella gospel innovators The Golden Gate Quartet.

African American Blues players were somewhat rare in the Charlotte sessions. Unlike areas of the deeper South where black people had regular radio shows, whites in Charlotte monopolized the airwaves until the late 1940s. Local white radio hosts such as Grady Cole at WBT loved black gospel quartets but seem to have had no use for the Blues. Unlike Durham, N.C., where white store owner J.B. Long nurtured Blues players and helped them get recording opportunities, Charlotte had no white Blues patron.

Detailed examination of the performers and songs from Charlotte’s Blues sessions is elsewhere in these liner notes, but it is interesting to note here the degree of interchange between black and white musicians in the Charlotte recordings. Jim and Andrew Baxter, whose fiddle-based Blues harked back to the 19th century, travelled up from Georgia along with the white Georgia Yellow Hammers string band and they recorded together on “G-Rag.” The pop culture references of the Cedar Creek Sheik and Virgil Childers sound quite similar to songs cut at the same sessions by white players such as Jimmie Davis and Cliff Carlisle. And the instrumental virtuosity of Luke Jordan’s “Church Bell Blues” and “Cocaine Blues” draws on the “crossover” sounds of ragtime, rather than the deep Blues heard in the Mississippi delta.

Eventually record companies would establish permanent Southern studios in Nashville in order to be close to radio powerhouse and its Grand Ole Opry. Charlotte would fade from the spotlight. But recording never stopped in the Queen City. Hometown bluesmen Wilbert Harrison and Nappy Brown had national hits in the 1950s. James Brown cut “Papa’s Got a Brand New Bag” in 1965, credited with launching Funk music. REM made their first LP “Murmur” at Charlotte’s Reflections Studios in the early 1980s, a landmark in the “Alternative Rock” wave. And who knows what’s bubbling today at half a dozen small studios around the city, from venerable Reflections to new Loco Sound, hub of the Carolinas’ growing Latino music scene.

— Tom Hanchett